The Absolute Importance of Choosing Better Verbs

Reader, I added that “absolute” in the title in hopes of gaining your attention. I worry that a blog post about simply choosing better verbs could be one you’d skip over. You already know this stuff, right? It’s basic, it’s assumed, it’s Writing 101.

But before you write off this article as rudimentary, I want to tell you that I’ve returned from the editing trenches, and I have news. Some of you are turning out manuscripts in which you’ve forgotten to go through and do a verb level-up. Using lesser verbs instead of better verbs shows itself in several ways.

We’ve all been sufficiently warned to limit our “to be” verbs (They’re useful, so don’t seek to eliminate them.). It’s a common and necessary endeavor to go through your manuscript and flag those buggers and then mull over whether or not you want to change or keep them. I want to go beyond that here—I want to talk about verbs that seem perfectly fine at first glance, but that upon further examination lack specificity and precision.

It’s fine for your lesser verbs to serve as placeholders. But if you don’t pay specific attention to your verb choices during revision, you’re going to end up with bloated phrasing, boring descriptions, and characters acting with inexactness. I want to look at each of these issues individually and explain why it’s so important that we choose better verbs.

BLOATED PHRASING

When we’re imprecise with our verbs, we can be tempted to over-describe, to keep refining what we’ve said so that our reader will understand. We say more than necessary. Of course we’ll use verb phrases in our writing, but sometimes phrases or even entire sentences exist simply to convey imprecise descriptions or actions. This imprecision will sabotage our efforts at concision.

Here’s a made-up example:

When I threatened to tell the boss, she came at me forcefully. She raised her fists and started punching me.

If the bolded phrase in the first sentence was more precise, we wouldn’t need to do so much modifying in the following sentence. Here’s a more concise version:

When I threatened to tell the boss, she attacked me. With her fists.

Now, if you’re doing something specific with voice, you might make the valid argument that your character/narrator talks with a certain affectation. That the wordiness is the point. But most of the time a verb, skillfully chosen, can save us from the need to write unnecessary modifications and explanations.

BORING DESCRIPTIONS

Using better verbs also means using more active verbs. It requires us to lean away from telling and into showing. And when we’re showing, we’re going to be looking for resonant images and significant details to convey to the reader. We’ll be leaning away from the cliché and vague and toward the fresh and specific.

One move I like, when used occasionally, is to let the non-living-things in your story do something. Instead of having those nouns sit passively on the page, give them a chance to interact with their surroundings.

Here’s an example of what I mean from Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch.

Faintly, I heard traffic singing on the street.

In this scene the character had just been listening to music while sharing earbuds with a girl he’s in love with. That he perceives the traffic as singing is the point of even noticing the sound. But you do want to be judicious with this type of thing—we don’t want our readers to start cringing at how our flowers smile and our clocks cry.

CHARACTERS ACTING WITH INEXACTNESS

Choosing better verbs isn’t about injecting literary firecrackers into your sentences (although on occasion that’s good) but rather replacing sufficient verbs with superior ones. Take a look at the following sentence from Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop. In this scene we’ve got a mob of journalists who have been waiting to vent their grievances on one Dr. Benito.

Then Dr. Benito arrived; he came from the main entrance and the journalists fell back to make way.

Had this been a sentence in my own work, I likely would have used the word “moved” or “stepped” instead of “fell”. And that would have been okay. But “fell” is more apt, because within a page or two the journalists acquiesce and effectively withdraw from the conflict. “Fell back” brings with it the connotation of unified movement and retreat. It’s a better verb.

Writing that seems to be trying too hard can be a problem, but so is being loose with word choices. I’m not talking about forcing lyricism or complexity into your sentences. But choosing better verbs, even simple ones, will almost certainly make your prose more vivid and vital.

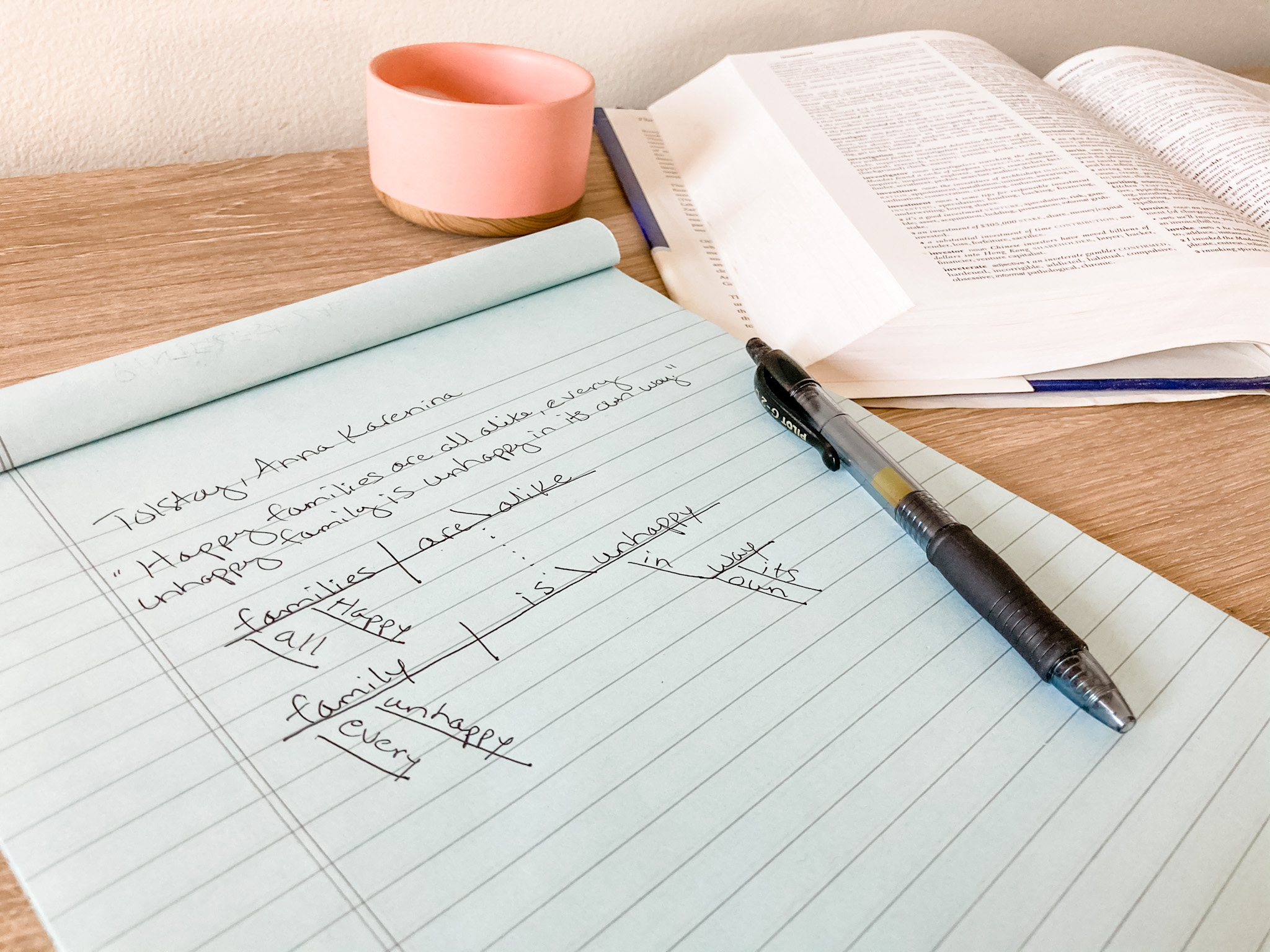

You know what verb I like? Fiddle. That’s what I encourage you to do. Strip your sentences down, one by one, to the simple subject and verb. Tinker around and see if you can tighten the connection between these fundamental components. No need to pressure yourself to come up with perfect verbs, but see if you can’t come up with better verbs.