Story Voice: The One Thing You Must Nail on the First Page

I was watching an episode of The Voice last night and I was thinking how the job of those singers and the job of a writer is pretty much the same. You’ve got a hot minute—less than a minute—to create some sort of experience your audience wants.

Contestants on The Voice start out by auditioning “blind.” They sing while the four celebrity judges listen with their backs turned. The judges can’t see what the singer looks like or how they are moving. Physical presentation and stage presence are irrelevant. The first impression is nothing but voice.

When a reader picks up your book, they won’t know your cast of characters, they won’t know in what direction the plot’s headed, they won’t have a connection to the world you’ve built for them. But they will start having an experience of your story voice from the first sentence.

Whatever bit of setting, glimpse of character, hint at plot that goes in to your story’s beginning, it will all be filtered through a narrative voice. That narrative voice, your story voice, needs to be so compelling that your reader will be willing to follow it for hundreds of pages.

Readers don’t fall in love with the facts of a story, they fall in love with a way of telling the facts of a story.

Now, a reader may not know exactly what it is they’re responding to. They might think that what they like is a situation, a dramatic moment, or just plain beautiful writing. But all of those things are conveyed through a narrative voice, which I will argue, is the most important thing to get right on page one.

Understand that when we talk about story voice we’re not simply talking about point of view. The issue is much greater than the decision of choosing a first or third-person narrator. And even in memoir a writer takes on a storytelling persona. Mary Karr says that memoir lives or dies based 100 percent on voice.

The narrative voice, a particular perspective arising from within the story, will convey an awareness of the story to the reader through things like syntax, diction, phrasing, tone, and choice of detail. The narrative voice is the way of telling.

In a work of fiction, you’ll decide who is telling your story and why. It’s important for you to remember that this who is never you, the author. Whether told from first or third person, this narrator will have a voice that you the writer must understand, believe in, and inhabit for your reader.

I just finished reading True Grit by Charles Portis. The facts conveyed in the first paragraph, narrated in first person, are that a fourteen-year-old girl from Arkansas has gone to seek revenge on the man who murdered her father and stole his horse and money.

Enough information at the start for me to keep reading? Maybe. I like westerns (of Lonesome Dove caliber), and revenge stories are of interest. But I also shy away from stories written for adults with child narrators (it’s a personal thing). The premise is solid, if less than exciting.

But let’s take a look at the way Charles Portis gives us those facts in the first paragraph and how the voice might be enticing us to read on:

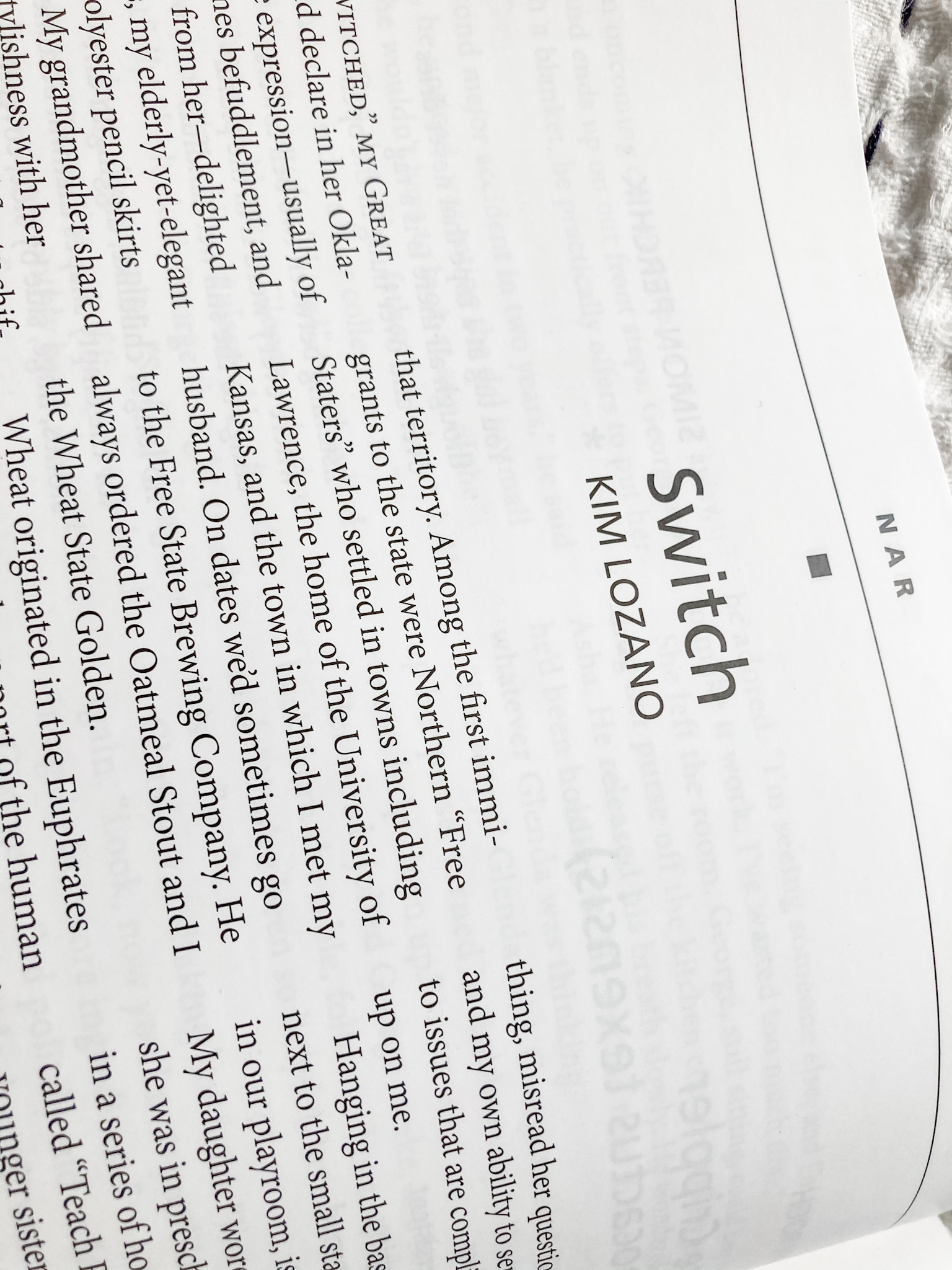

People do not give it credence that a fourteen-year-old girl could leave home and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood but it did not seem so strange then, although I will say it did not happen every day. I was just fourteen years of age when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.

- We know from “I was just fourteen years of age…” that a grown narrator is telling a story from the past, so we’ll get the youthful experience filtered through her older self.

- Twice she mentions that she is fourteen in this tale she’s about to tell. If she isn’t preoccupied with her age, she knows that others are.

- The language and syntax is formal and emphatic. Right from the beginning with, “People do not give it credence…” I’m catching a snooty air.

- Rather than a revenge story that’s born solely out of anger or grief, the last phrase of the paragraph lets us know that this quest is a moral imperative for her. There’s a certain indignance in “and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.”

When Charles Portis presents us with the voice of Mattie Ross, he’s giving us bits of a cast of characters, setting, and plot, but he’s giving it to us through a specific tone and emotional distance, not just to his character, but to the reader.

I propose that you as a writer, when you offer a reader your first page, are in the same situation not just as Charles Portis, but as those singers on the The Voice stage. When the judge likes what she hears, she turns her chair. With your book, your reader will turn the page. And you’ll have made it to the next round.