Writing Lessons from LITTLE, by Edward Carey

How lucky I am that I came across Little, by Edward Carey, while digging around on the internet for book recommendations. My Google search phrases must have included the words “brilliant”, “absurd”, and “hilarious”, because this book is all these things. Little is the dark and dazzling story of the young orphan girl who becomes the legendary wax sculptor, Madame Tussaud.

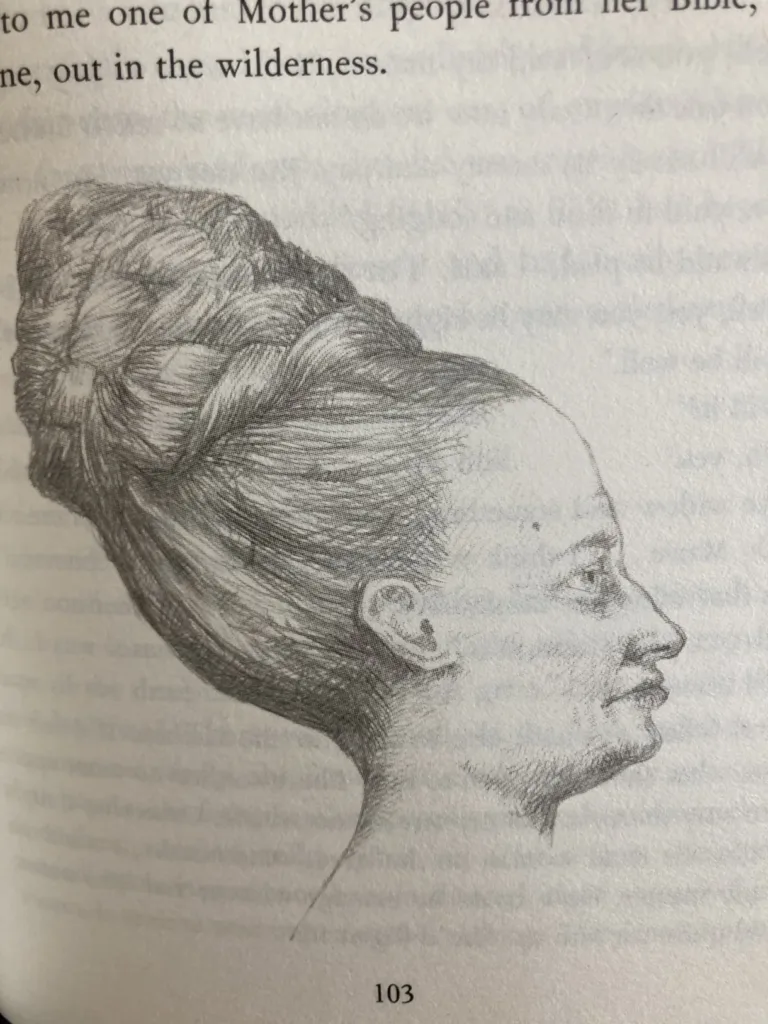

Little is one of the wittiest books I’ve ever read (although it’s tragic) with a kind of Monty-Python-as-macabre-literature vibe. And oh, Carey’s drawings…Initially, I read the book for pleasure. This time around I’m reading it for writing instruction, and I thought I’d share with you some lessons this novel has to offer.

1—Utilize the Power of a List

The 155-word opening paragraph of Little is one long sentence. Basically, it’s a list of significant events, people, and goings-on in 1761—

In the same year that the five-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote his Minuet for Harpsichord, in the precise year when the British captured Pondicherry in India from the French, in the exact year in which the melody for “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” was first published, in that very year, which is to say 1761, whilst in the city of Paris people at their salons told tales of beasts in castles and men with blue beards and beauties that would not wake and cats in boots and slippers made of glass and youngest children with tufts in their hair and daughters wrapped in donkey skin, and whilst in London people at their clubs discussed the coronation of King George III and Queen Charlotte: many miles away from all this activity, in a small village in Alsace, in the presence of a ruddy midwife, two village maids, and a terrified mother, was born a certain undersized baby.

The end of a sentence in general, and the last spot on this list in particular, can be viewed as the VIP parking spot. It’s where you put your most important information, the thing your sentence has been building toward. Carey could have tied baby Marie’s birth to one historic signpost, perhaps just Mozart’s minuet or the roots of the French Revolution. But the robust list doesn’t only emphasize the significance of the year. Putting the birth of this “certain undersized baby” at the end implies that she’s going to earn her place on it.

2—Find Genius in Gesture

We really only have a couple of ways to communicate to each other who we are—the things we say and how we act. Here’s an example of using gesture, in a paragraph that’s so good I want to marry it—

Curtius’ chest hunched; I thought he was toppling forward. Then he drew his long arms inward and there was a very small and completely silent joining of hands together, twice. To the uninitiated, it may have appeared that he was secretly squashing something small, a fly perhaps, a frog, a snail, a kitten, whereas actually he was clapping.

How would a writer best describe the peculiar physical motions of a person who grew up not observing other people but only wax heads? This paragraph is how. Curtius’ actions here convey that he has no idea how to behave, how to move his body normally. When you’re working on a scene, identify for yourself what you want to convey through your character’s actions. Challenge yourself to move beyond shrugs and smiles and really describe the specific and unique ways in which people move.

3—Dig Deeper When “Showing”

In this scene, Carey needs to do a seemingly simple thing—convey the alarm that young Marie feels at the growing closeness between her mentor, Doctor Curtius, and her nemesis, the widow Charlotte—

Returning to the workshop whenever I could, I discovered new and terrible progressions. Her tools, for one, had joined his upon the table. To begin with they kept to one side, but later it was those different tools, his and hers, moving closer and becoming acquainted. Once I saw the widow reach out and take a hold of Doctor Curtius’ trocar, the trocar with the straight shank, which was designed to penetrate the skin to evacuate deep abscesses, but was used very successfully by Curtius for making passages in wax ears. The widow took this object up and used it to penetrate calico. But that was not all: incredibly, Curtius sometimes borrowed the widow’s narrow buttonhole hooks and used them to draw out nostrils. And so, it will be understood, I had to take action before it was too late.

A Writing 101 principle is “show don’t tell.” Yes, there are exceptions, but most writers don’t struggle with the exceptions, they struggle to show their subjects and moments vividly and memorably. In Carey’s paragraph there’s no mention of Marie feeling threatened, vulnerable, or endangered. Yet it’s all there in her description of Curtius and the widow’s newly-mingled tools. And where a lesser writer might have tried to do this in a sentence, to imply what’s going in in the relationship with a single description of their tools, Carey goes on for a paragraph. He mines the moment not just for meaning, but for entertainment.

4—Go for the Offbeat and Oddball

One thing Carey doesn’t allow is for his characters to simply have interests. They have obsessions. His Dr. Curtius isn’t just consumed with creating wax heads, he’s infatuated with the living heads from which they’re patterned—

She seemed to register how Curtius cared, how concerned he was for all the chins and ears, how he sympathized with every fold of flesh. Curtius was in love with eyelids and lips; he would swoon over an eyebrow, fidget in excitement as a mole or dimple. If a subject had two or three small hairs beneath his nose missed by the barber, Curtius would ensure that they were a part of the finished head. It did not matter if the head he was making has burst corpuscles around the nose, or pores so large they could be seen several paces off; it didn’t matter if the head was wall-eyed, or the skin was so shiny that the wax must be varnished to suggest patches of sweat: whoever came to him, Curtius loved.

If the rest of us are trying to make sure we’ve got at least one quirky or strange character in our story, Carey makes sure all of his are. That every character in this book is some version of weird is one of the things I adored most about it. Whatever peculiar vision you have for a character, I encourage you to use Little as an example and nudge your story people ever further toward that edge.

5—Allow for Audacity

In the following passage of dialogue, there’s an absurd secondary thing that’s going on while the widow Charlotte (in love with her dead husband) speaks to her colleague and beneficiary Dr. Curtius (in love with the widow Charlotte). She’s just directed her son Edmond to comb her hair, and while she speaks to Curtius, she interjects comments to her son, which I’ve bolded. The condensed version—

“Attend me, please. I Charlotte, widowed piece of womanhood that I am, mean to educate you, Doctor Curtius. We are known to each other now, we have business in common, and so I shall let myself a little down.”

“We are known to each other, yes! To each other!”

“Edmond, comb, comb away. I reveal myself to you, sir, through the biography of a business. I shall talk to you of my husband.”

“Oh, yes?” was the doleful response.

“My Henri Picot’s parents dealt in secondhand clothes. That was the beginning. They had a little shop here in the Faubourg San-Marcel. That is the essential beginning.

“Comb, Edmond, harder.

“The first thing you learn about a secondhand-clothes shop is that is must be kept very dark inside…

“But comb, Edmond, do!

“We sold undershirts that people had died in, panniers of prostitutes, old greasy bonnets belonging to shrunken widows who’d finally given up the ghost. Stockings very mended. Old clothes that had been used, that other bodies had pushed themselves into…

“At our shop, we’d see people trying to climb up the slippery ladder of Paris. A market girl would put on the lace cap of a dead lawyer’s wife…Sometimes at night, when his parents were snoring, Henri and I would go into the store and try things on ourselves. He would dress me up as a lady.

“Plait, Edmond, tight! Tight!

…Now listen to this Doctor, attend particularly…We have work making busts. You are very skilled, Doctor Curtius, everyone can see that,…Here we are at a crossroads, you and I…We attempt to take two steps up society’s great ladder. And my question is this: Will you come with me?”

“Yes, yes, I will!” There was no pause.

“Will you hold tight and not let go?”

“I will, I will by all means…”

“…A business has gone under, and it makes way for us. Let us not follow it. So, Doctor Curtius, float or drown.”

“Float! Float!”

“Edmond, you may return my bonnet.”

There’s a strange and hilarious escalation—almost sexual in effect—as the widow attempts to convince Curtius to do what she wants while ordering her son to properly attend to her hair. How brilliantly the intensification of her appeal to Curtius is channeled into her increasingly ecstatic commands to her son about his coiffing. And then that final line with its postcoital overtones. I laughed. I cringed. Pledge with me, writers, to be more audacious in our storytelling.

6—Be Bold with Metaphor

Sometimes a metaphor fails because the comparison being made just doesn’t feel spot on. Is this first thing really enough like the second thing, we’ll wonder. O sometimes the metaphor seems too ordinary or is an outright cliché. But Carey is a skilled metaphor-tician. Take a look at this simile—

I came to know Doctor Mesmer, not in person, but in wax. He had a very flat face with almost no profile at all, as if it had been grown facedown in a skillet.

Had he written “…as if it had been hit with a skillet,” I wouldn’t have questioned it. But hitting things with skillets is somewhat common in stories and cartoons—a passable metaphor, if familiar. But a face that looks like it’s been grown in a skillet is a metaphor I’ve never heard before. Such a wonderful image. Apt and surprising!

7—Delight with Unexpected Description

To double down on the advice to be bold and surprising, it’s worth the effort to come up with details that are unexpected. In the following description, Carey had to decide what about this character made her “ugly”—

These were the long seasons of Madame de Polignac. Dian de Polignac, sister-in-law of the queen’s newest favorite, was an ugly woman, hunchbacked and slovenly, with sallow skin and wet lips; she swallowed when she saw men.

Those wet lips! And for good measure he keeps going with “she swallowed when she saw men.” This is just great writing. And Carey didn’t even need to fire up the metaphor machine. These kinds of details can be simple descriptions that will delight readers when they’re unanticipated.

Yes, Little is a tightly crafted novel. But I think the real lesson it offers to writers is to let loose the reigns during the drafting process. Allow yourself to play. Try something brazen and original. Follow the example of Little and write big.